When one goes to google “trash art”, one finds themselves in front of a variety of articles - and many of them pose the question: is art trash? Or something more precisely, such as: is contemporary art rubbish? While this might be the topic of another, quite vast conversation, our article today will focus on trash as a means, and not as a concept, in contemporary art. In order to try and understand how and why trash is being used in artistic practices, and who those engaging in these practices are, we will of course also mention other terms related to our aforementioned search, like “junk art” or “recycled art”. In the age of global warming and the conversations on the burning existential questions of our time, these questions pose themselves as rather important ones, where using waste and recycled materials to make art is not only a creative statement, but a socio-political one as well.

But even though talking about Trash Art at this very moment holds a certain kind of relevance, the concept itself is certainly not a novelty. Many of our readers have probably already seen an example of trash art, perhaps without being aware of it; I know that one of the very first works of art I ever encountered could fall into the category, and I will come to mention it later in the text.

The History of Trash in Art

Visual artists have been experimenting litter throughout history, from the early Avant-garde to today, both inside and outside of the academic circles. In regards to the former, it could be traced back to the beginning of the 20th century, when the very definition changed and its traditional understandings were abandoned; art began looking more and more like everyday life, by employing mundane objects and new techniques. One of these was collage, which meant putting pieces of paper, cardboard and other “light” found materials together to create compositions. The proponent of the early Cubism, among them Braque and Picasso, made collages such as these, and even used discarded elements such as pieces of cloth or rope as part of their paintings - essentially making what Jean Dubuffet will later call an “assemblage”. Similar intentions can also be found among the Dadaists such as Raoul Hausmann and Kurt Schwitters, whose artworks made of found objects functioned as commentary on industrialism and consumerism, for example. Speaking of Dadaists, we cannot not mention Marcel Duchamp’s radical ready-mades, “The Fountain” or “Bicycle Wheel” among the most noted ones which, in truth, may have not used a thrown-out pissoir or a wheel, but it was sure enough that these were given a new purpose and meaning, very far from their initial ones.

From the 1920s onward, there were many other big names who were working outside of the canons of what art should be made of, with, and what it should look like. We could mention the Surrealists like Meret Oppenheim, the Contructivists such as Naum Gabo, the Informelist Alberto Burri, the American Neo-Dada legends like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg (just take a look at his Monogram from 1955-59, which features a stuffed goat in a manner that couldn't be move evident. It is also well known that Rauschenberg often walked the streets of New York, collecting scrapped materials from the streets and putting them straight into his works.) Indeed, the post-war art seems to be all about a kind of rebellion which meant dealing with reality in the most direct of ways, as opposed to the increasing influence of Abstraction and Abstract Expressionism. Nouveau Realisme’s Arman, on the other hand, used literal trash in his art at the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s - his “Poubelles” series features garbage inside hermetically sealed transparent boxes. Of course, the more famous works of art by Arman are those in which musical instruments are often broken and falling apart. Finally, how could we not mention Piero Manzoni and his “Artist’s Shit”? Although we can still question the actual existence of human feces inside that tin can, the idea that something like that could be used in the creation of a work of art should not, and could not, be ignored as significant in the Trash art discourse.

Contemporary Trash Art

The notions of Trash art as we know it today can also be found in the roots of other movements of the last century, particularly in the initiatives that emphasized the process of making art, rather than the product of it. These include Fluxus, but also of course Process art and Mail art, all of which saw garbage as one of the regular ways to make art. They supported the idea of an artwork that is alive, ephemeral, and in a constant state of change. The Italian Arte Povera continues this dialog (Michelangelo Pistoletto’s “Venus of the Rags” comes to mind), and then there is the whole of Conceptual art movement, in which an artwork’s idea was in the spotlight, expressed through a variety of tools (among which were found objects and rubbish as well). Many artists deal with the topics of memory, for instance, by including discarded objects from the past in their installations, or create entire new/old environments, like Joseph Beuys did.

Until the 1980s, and especially after, an important aspect of the use of trash and recycled materials in art was the fact that it reflected on the state of the world, and the state of the places they were made in. Trash artworks of the last four decades give us proper history lessons: we see the rise of environmental art as one of the more direct protagonists, but also other Post-Modernists tendencies in which there is an elevated awareness of the ecological issues. Many artists begin incorporating found plastic in their work, among them Kim MacConnel, Tony Cragg and Julian Schnabel, and the term “trash art” becomes a frequently used one in the titles of the art exhibitions held during the 1990s in the United States.

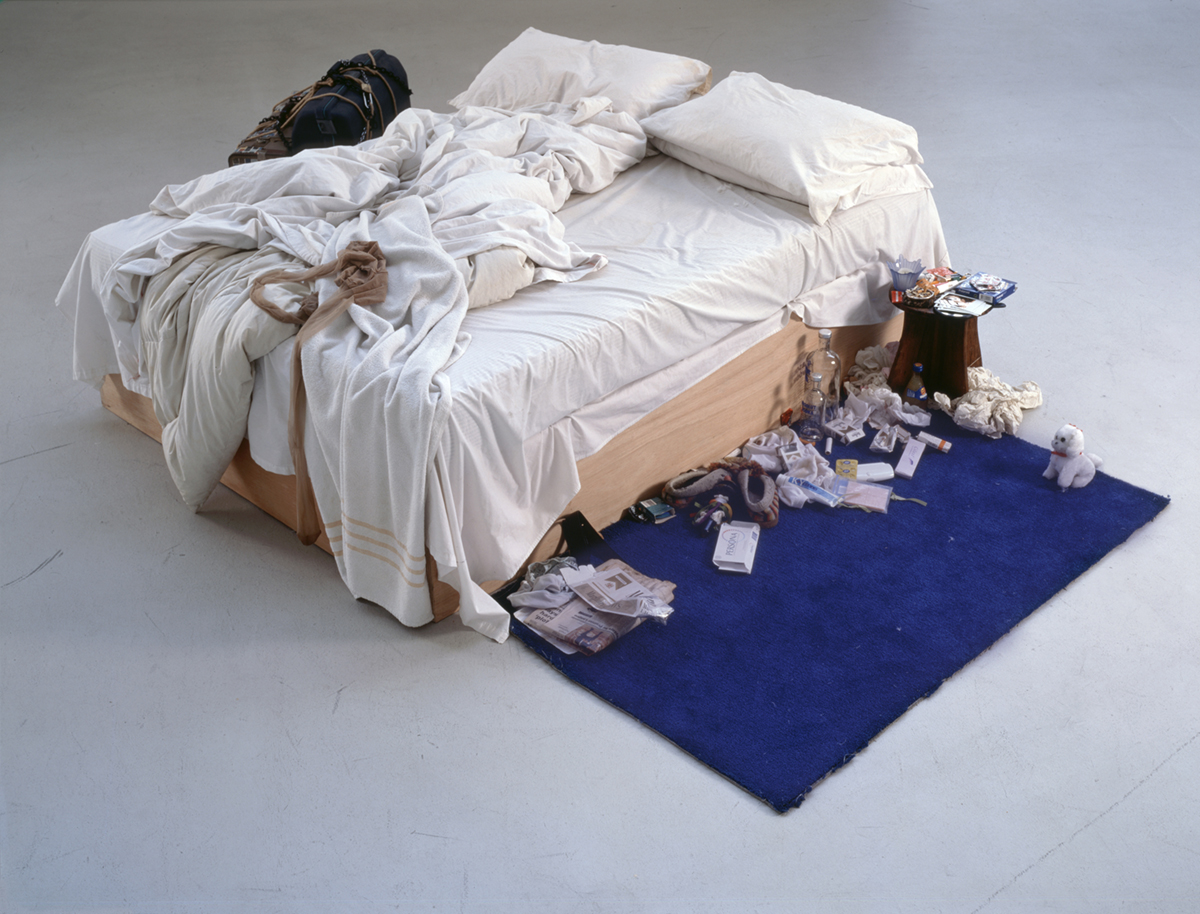

A decade charged with significant political events, the 1990s brought a sort of art in which trash, or simply usual objects, were practically the new normal, put there to transmit direct messages to their audience, messages that convey raw emotions and notions of modernity. Here we have the YBAs, or the Young British Artists like Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, Marc Quinn and Tracey Emin, whose messy bed surrounded by rubbish became one of the catalysts of its time.

Artists of Junk Art Today

The YBAs came to influence artists Tim Noble and Susan Webster to create “Dirty White Trash (With Gulls)” in 1998, in which “6 months’ of artists’ trash” is constructed so that its shadow on the wall behind, when the work is lit from a certain angle, amounts to two people (the artists themselves) sitting back to back. The work proposes an interesting look at self-portraiture, at the same time putting a pile of trash away from nature, in however small amount.

Up until this point, this Noble and Webster artwork is basically the most literal example of Trash art; these artists worked exclusively with trash, as opposed to those whose oeuvres contained trash only in addition to other materials. Today, we can finally talk about other creatives who followed in their footsteps, dedicating themselves completely to the concept of waste in its literal sense.

John Chamberlain’s sculptures, for instance, were always made entirely of industrial scraps, most notably old automobiles and their parts - bumpers, fenders, roofs - welded together. Michelle Reader uses recycled materials to create toy animals and other sculptures, similarly to Robert Bradford who, in turn, uses old toys to make sculptures. Korean artist Choi Jeong Hwa produces large-scale installations and public artworks using recycled waste, reminding me of the work of a Portuguese street artist, Bordalo II, who mounts painted garbage elements onto walls to create animal portraits.

But if we are talking about the most important figures of Trash art today, we simply must dedicate an entire paragraph to Vik Muniz, a Brazilian artist whose project titled “Waste Land” is one of the movement’s landmarks. As hinted by the title of this documentary, Muniz spends three years searching the waste areas, in this particular case the world’s largest garbage dump Jardim Gramacho, found in the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, interacting with “catadores”, the self-designated recyclable material pickers. Muniz ends up creating a collaborative project with these inspiring characters by creating their portraits out of the very items they picked up. The artist donated all proceeds from the auction sale of these works back to the catadores, improving their labor union.

In conclusion…

Although Muniz’s project turned into one of Trash art “by accident” (he initially planed to paint the catadores’ portraits on canvas), it speaks volumes in terms of different kinds of artistic engagement that an artwork can bring up. When it comes to Trash art, the connection between the artist and their work seems to become an intimate one, even more so than usual - it is strongly determined by circumstance, both geographical and social, and it comes to tell a very palpable story of people, and the artists themselves.

The relationship between the work and its audience is a particular one here as well. The spectators get re-introduced to a thing they had already let go of, the thing that is now showing them another, different side of itself, more often than not a more beautiful one than before. Artists become true saviors and collectors of society’s droppings, creating an attentive archive that carries strong statements. The idea of reusing, repurposing, giving new life to something that’s been rejected and thrown out has both practical and psychological connotations, as it creates strong symbolism and value to the human experience that should not be ignored - if anything, it should be celebrated.

Stay Tuned to Kooness magazine for more exciting news from the art world.